ADVERTISEMENT

Oftentimes, with "provenance watches," the conversation is centered around potential value. We see rare birds come up at auction: Paul Newman's Paul Newman Daytona, or, more recently, Al Capone's Patek Philippe, and we're forced to think about what the watch plus the story could possibly be worth. Rarely do we think about what that watch meant to the owner, the man or woman we're looking at with such reverence or interest. Naturally, we are concerned with its value to the market today because it would be nearly impossible to understand the value that the person placed on the watch during their lifetime. This is a story about the profound value an extraordinary owner bestowed on their watch.

With a tip from a friend, a visit to The Met, and some personal research, I uncovered the story of Frederick Douglass's first watch and what it meant to him, in his own words.

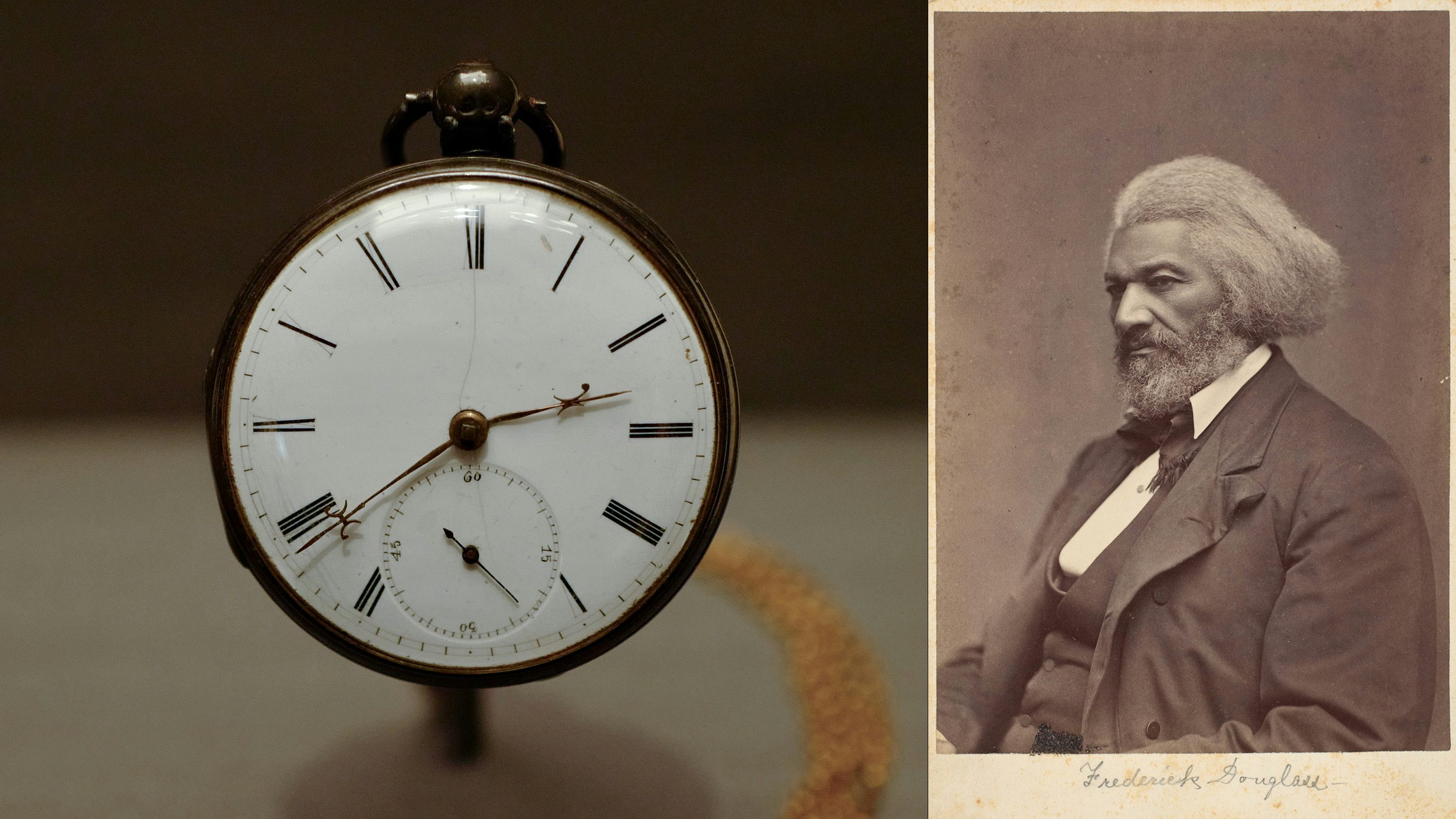

The watch itself might be passed over by many at a glance. The dial is unsigned, and it is encased in silver with a gold chain; Douglass purchased the watch in Belfast, Ireland, in 1846 for $40, eight years after escaping slavery. The watch is displayed alongside a full ensemble — Douglass's Melton wool tailcoat, British top hat, and sunglasses — as part of The Met's "Superfine: Tailoring Black Style" exhibition. Celebrated at this year's Met Gala, the exhibition was curated by Monica L. Miller and conceived by Andrew Bolton. It traces the lineage of Black dandyism: the art of dressing with precision, intention, and self-possession.

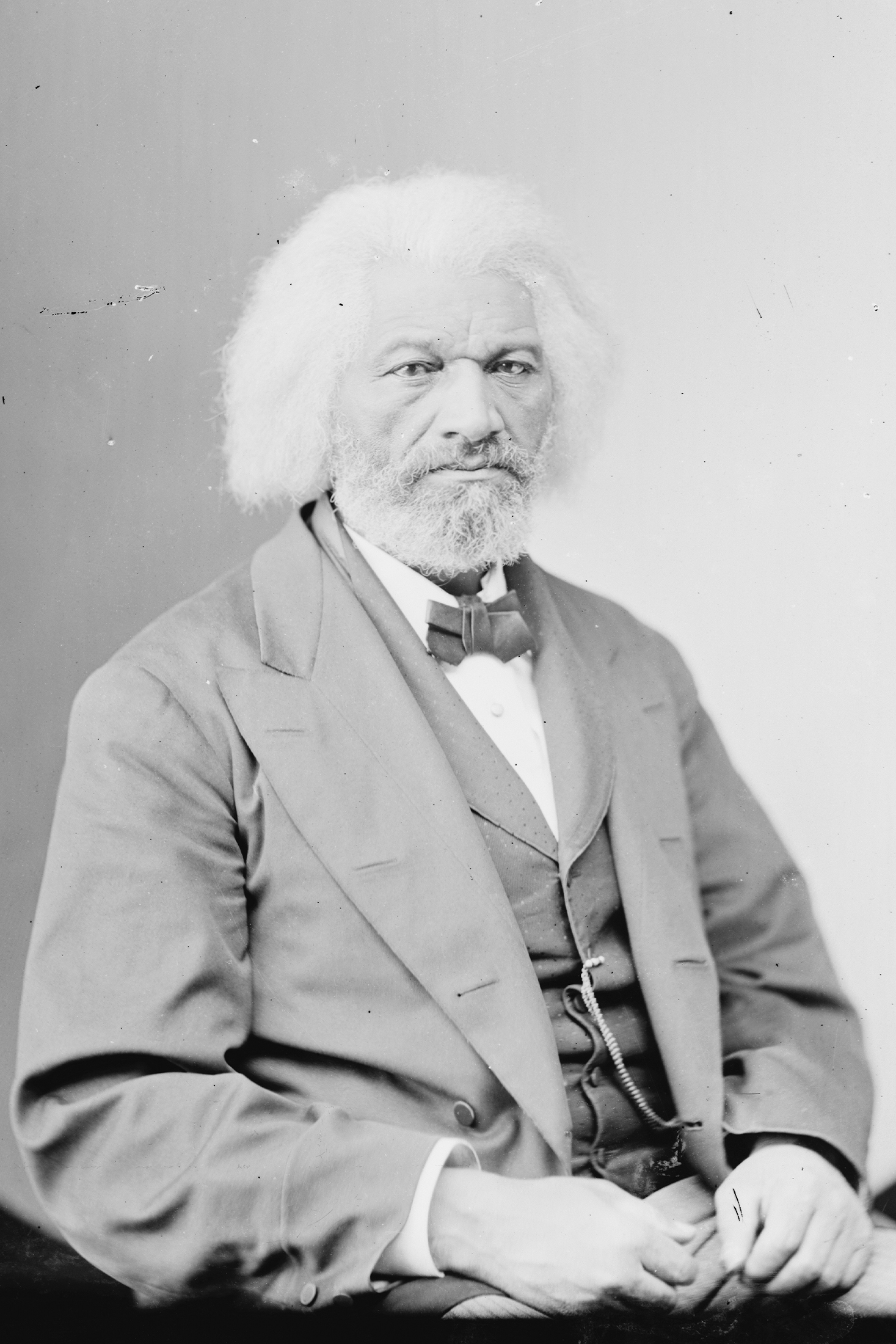

Douglass was a formerly enslaved African American who became one of the most influential abolitionists, writers, and orators of the 19th century. After escaping slavery in Maryland, he rose to international prominence for his powerful autobiographies, speeches, and activism against slavery and racial injustice. As a free man, his public image was intentionally tailored, cultivating a polished, formal image. Douglass is known to be the most photographed American of the 19th century. Using photography as a medium of self-presentation, he never smiled in portraits; rather, he believed the seriousness of his expression countered minstrel caricatures and conveyed the gravity of his political mission.

Frederick Douglass photographed in ca. 1877

Image courtesy of Brady-Handy photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

A relentless advocate for freedom, education, and civil rights, Douglass became a symbol of Black self-determination and dignity in America and abroad. In many of those now-famous portraits, Douglass's pocket watch chain is clearly on display. Watches, more broadly, played at least a part in Douglass's life; he is believed to have gifted another to abolitionist John Brown. Brown was wearing the Waltham pocket watch when he was executed in 1859 for the raid on Harper's Ferry.

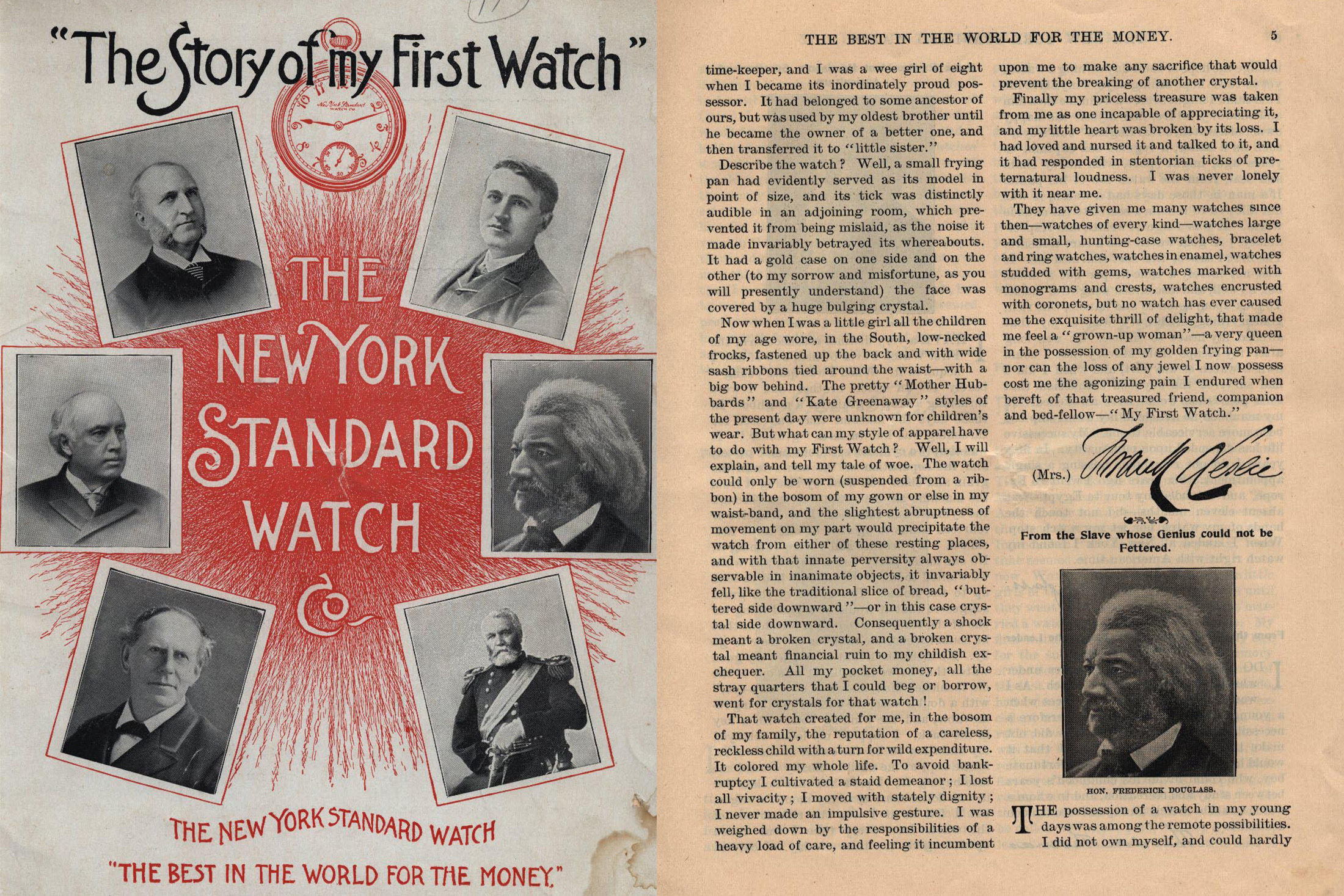

Viewing a watch in a museum is one thing, but more important is the essay below, written by Douglass and published in 1894. These words were included in a pamphlet distributed by the New York Standard Watch Company entitled "The Story of my First Watch," alongside the personal stories of many prominent figures of the time, like Grover Cleveland and Thomas Edison. In context, this is one of the most compelling watch stories we've encountered in some time. That's why we're publishing Douglass's words in full, as a powerful reminder of what a watch can stand for. Beyond the specs and price tags, it's the personal meaning we attach to these objects that keeps us coming back to a place like Hodinkee.

Image courtesy of Pocket Watch Database

From the Slave whose Genius could not be Fettered

The possession of a watch in my young days was among the remote possibilities. I did not own myself, and could hardly indulge the hope of some day owning a watch, yet in those hope-killing days of my slave life I did think I might somewhere in the then dim and shadowy future, find myself the happy owner of a watch, a real English "bull's-eye," such as a sailor, a regular sea captain, 65 years ago, might sport, with heavy chain and seal, from the watch fob of his pants. If a man in those days had a watch, it was not allowed to remain a secret to the outside world. It was a sign of wealth and respectability. A gold watch was a rare treasure. The first I saw of this sort charmed me. It was not merely a time-keeper but a music box as well, and discoursed delightful music. To look upon, listen to and handle, this rich, golden thing of beauty was a joy that swelled my heart to silence. It was long after my escape from slavery that I could own a watch of any sort, and when I did I had survived the boyhood enthusiasm that such possession would have awakened. In my manhood no article in my ownership has been more serviceable to me. My successive life has depended upon punctuality. In fifty years I do not remember missing a single appointment. Six years ago I went to Europe, and extended my tour to Egypt–was absent eleven months–did not touch the hands of my watch nor let my watch stop. When I landed at New York I found my watch right with American time.

Top Discussions

Breaking NewsA Yellow Gold Rolex ref. 6062 Sets Record for the Reference, Third Most Expensive Rolex Ever Sold, At $6.2 Million

Photo ReportInside Mike Wood’s ‘For Exhibition Only’: A Private Rolex Collection On Limited Display

Reading Time at HSNY: Ex Libris